Sustainable Microservices Through Separation: A Disciplined Approach to Business Logic

Abstract

Modern software systems require not only functionality, but structural sustainability. As services scale and teams grow, architectural clarity becomes more valuable than technical novelty. This essay presents a disciplined approach to microservice design based on explicit separation of concerns, metadata-driven contracts, and infrastructure agnosticism — enabling long-term adaptability without compromising domain purity.

At the heart of this approach lies the application business rules layer, a core component often diluted or entangled within frameworks and delivery mechanisms. Grounded in Clean Architecture and Hexagonal Architecture principles, this work explores how to implement this layer independently of frameworks, databases, or transport layers. By isolating business logic in framework-agnostic use cases, exposing ports for external communication, and enforcing validation and observability within the core, we build systems that are robust, testable, and evolvable. The techniques and patterns described are applicable across programming languages and environments, forming a universal foundation for sustainable backend development.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework: Clean Architecture and Hexagonal Boundaries

- Designing the Application Core: Use Cases, Ports, and Isolation

- Integrating Delivery and Infrastructure

- Metadata as Architectural Communication

- Call to Action: Embrace the Bisslog Mindset

- Common Pitfalls and Anti-Patterns

- Conclusion: Designing for Longevity, Not Just Delivery

- References

1. Introduction

Many modern backend frameworks provide integrated solutions for exposing APIs, handling requests, validating inputs, and interacting with external systems. However, they tend to obscure where the business logic lives and how it interacts with the rest of the system. More concerningly, they often encourage embedding business rules directly inside HTTP controllers, handlers, or serverless functions.

This design pattern creates code that is difficult to test in isolation, hard to reuse across different delivery mechanisms (e.g., HTTP, CLI, message queues), and fragile when migrating to new technologies.

This article explores how to isolate business logic in a way that is:

- Independent of frameworks

- Centered on domain concerns

- Easy to test and evolve

To do this, we base our work on Clean Architecture and the Hexagonal Architecture, blending theoretical rigor with practical software engineering patterns.

2. Theoretical Framework: Clean Architecture and Hexagonal Boundaries

Modern software architecture has evolved in response to a recurring challenge: how to build systems that function correctly today, yet remain adaptable tomorrow. This challenge is not new — but as systems scale in complexity, team size, and integration surface, the need for structural sustainability becomes increasingly critical.

Two complementary architectural models have emerged as foundational responses to this challenge: Clean Architecture by Robert C. Martin (2012) and Hexagonal Architecture by Alistair Cockburn (2005). These models do not prescribe tools or technologies; instead, they propose clear boundaries, directional dependencies, and inversion of control as guiding principles for sustainable system design.

2.1 Clean Architecture: Layers of Intent and Independence

Robert C. Martin’s Clean Architecture emphasizes organizing code by responsibility, not by technology. It proposes a layered architecture with the following properties:

- Independence from frameworks: The core business rules must not rely on any particular library or framework. Frameworks are delivery mechanisms, not foundational structures.

- Testability by isolation: Business logic can be tested without databases, web servers, or real integrations — enabling faster and more reliable development cycles.

- Interface independence: Whether the application is accessed via REST, gRPC, CLI, or message queue should not affect the domain logic.

- Separation of concerns: Each layer has a singular responsibility and depends only on the layers inward from it — never outward.

At the heart of this model lies the application business rules layer, also known as the use case layer. This layer:

- Orchestrates operations based on user or system intent

- Coordinates interaction between domain models and external systems (via ports)

- Encapsulates workflows that define how the system behaves under certain conditions

When implemented correctly, this layer becomes the most stable and reusable component of the application — and the only one that encodes the system’s essential value.

2.2 Hexagonal Architecture: Ports and Adapters

Alistair Cockburn’s Hexagonal Architecture (also known as Ports and Adapters) expands on this by emphasizing how systems interact with their environment.

Rather than organizing around layers, this model organizes around boundaries. The system’s core logic is surrounded by ports (defined interfaces) and adapters (implementation of those interfaces).

There are two types of adapters:

- Primary (driving) adapters: These initiate interactions with the system (e.g., an HTTP controller, CLI command, or event handler).

- Secondary (driven) adapters: These respond to the system’s needs (e.g., databases, email services, message brokers).

Ports define what the core expects or provides — and are typically expressed as abstract interfaces or protocols.

This model enables:

- Reversible integration: You can replace any adapter (e.g., switch from MongoDB to DynamoDB) without altering core logic.

- Symmetry: Input and output mechanisms are treated equally as external concerns.

- High cohesion: The application’s core remains focused on expressing business value — not wiring, configuration, or I/O.

2.3 Metadata as an Architectural Contract

While Clean and Hexagonal architectures define structural boundaries, maintaining those boundaries at scale requires more than just disciplined code — it requires shared context.

In this discipline, we treat metadata not as runtime configuration, but as a design contract: a structured and versioned way to express which use cases exist, how they interact with external systems, and what behaviors they are expected to uphold.

This metadata may describe:

- The entry point of a use case (e.g., event trigger, HTTP route)

- Its external dependencies (e.g., outbound ports)

- Expected response semantics, side effects, or observability requirements

By declaring this information outside of code, architecture becomes more visible, introspectable, and automatable — both by tools and collaborators. It also decouples high-level intent from low-level implementation, reinforcing the principles of Clean and Hexagonal designs.

When treated as a shared artifact, metadata fosters alignment between architecture and implementation, without requiring constant synchronous coordination. It becomes a communication layer for scaling architectural decisions across teams and systems.

2.4 Complementarity and Application

Although these models use different metaphors (layers vs. hexagons), they are not in conflict — in fact, they reinforce each other.

Clean Architecture tells us how to structure the logic, from the inside out.

Hexagonal Architecture tells us how to shield that logic, from the outside in.

Combined, they produce a system in which:

- Use cases are central and fully decoupled from delivery and infrastructure

- Ports define contracts for external collaboration

- Adapters translate between implementation details and core expectations

- Metadata expresses architectural intent, making it accessible for inspection, validation, and automation

These ideas form the theoretical backbone for designing microservices that are coherent, composable, and long-lived.

3. Designing the Application Core: Use Cases, Ports, and Isolation

Having established a theoretical foundation grounded in Clean and Hexagonal Architectures, we now turn to the practical structure of the application core — the layer where business intent is modeled, orchestrated, and protected from external concerns.

This section explores the structure and role of use cases, the importance of ports as boundaries, and how isolation at this layer enables a sustainable, testable, and framework-agnostic system.

3.1 Use Cases as Coordinators of Behavior

In this architecture, a use case is not merely a function — it is the central unit of application behavior. Each use case encapsulates:

- A specific system intention (e.g., “register a user”, “create an order”)

- Input validation (or delegation to validators)

- Orchestration of domain entities and services

- Interaction with external systems via ports

- Output generation or domain-specific error signaling

Use cases are pure and self-contained. They do not know how they are invoked (HTTP, CLI, event), and they do not know how their dependencies are implemented. This purity makes them ideal candidates for:

- Unit testing without mocks of frameworks

- Execution in multiple delivery environments (e.g., serverless, background jobs)

- Reuse across contexts (e.g., internal APIs, scheduled processes)

[{Example: structure of a use case as a class with a single execute method taking validated input and returning output}]

3.2 Defining Ports for External Collaboration

To communicate with anything outside the application core — databases, queues, file systems, APIs — the use case relies on ports.

A port is a declared interface or protocol that describes:

- What functionality the use case needs

- What information it provides or expects

- What invariants must be respected (e.g., idempotency, retry safety)

Ports do not define how the operation works — they only define what is expected. This abstraction:

- Decouples logic from infrastructure

- Enables mocking and substitution during tests

- Facilitates parallel development between domain and adapter teams

[{Example: interface for a UserRepository port and its usage inside a use case}]

3.3 Avoiding Framework Leakage

A core objective of this design is to prevent framework logic from leaking into the application core.

This means no references to:

- Request objects or HTTP status codes

- ORM models or database sessions

- Logging or telemetry SDKs

All such interactions should occur through ports, with adapters translating between the framework’s idioms and the core’s expectations. This discipline:

- Reduces coupling and makes migration feasible

- Clarifies the boundaries of concern

- Forces thoughtful interface design

[{Example: showing the wrong way (coupled use case) vs. the right way (using a port)}]

3.4 The Role of Isolation in Business Logic Longevity

Why isolate business logic in this way?

Because business rules change slower than infrastructure, and isolating them ensures:

- Resilience to tech churn (framework upgrades, tool replacements)

- Predictable evolution of core logic without ripple effects

- Portability across execution environments

- Collaborative clarity between roles and components

By treating the application core as a protected space, we maximize its longevity and clarity. This is not an academic exercise — it’s a long-term investment in the maintainability and integrity of our systems.

This layered, isolated design of the core sets the stage for disciplined integration with external technologies — the topic we address next.

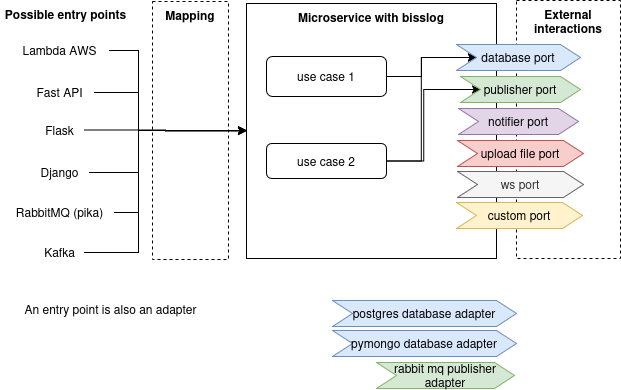

Figure 1. Entry points (such as Flask, FastAPI, or Kafka consumers) map to use cases via adapters. Each use case interacts with external systems through well-defined ports, which are implemented by technology-specific adapters.

4. Integrating Delivery and Infrastructure

Adapters connect the core logic of a microservice to its environment: handling inputs, executing side effects, and enabling real-world functionality — all while preserving the autonomy of the application business rules.

Following the principles of Clean and Hexagonal Architecture, we organize these adapters into two types: driving and driven.

4.1 Driving Adapters: Invoking the Core

Driving adapters initiate the execution of a use case. They interpret external signals (e.g., HTTP requests, events) and convert them into structured inputs for the core logic.

Common examples include:

- REST controllers

- AWS Lambda or cloud handlers

- Kafka or RabbitMQ consumers

- CLI interfaces

These components are responsible for:

- Decoding the external protocol

- Validating or parsing input

- Invoking the appropriate use case

- Encoding the response

[{Example: HTTP POST handler that validates input and calls a use case}]

Importantly, the use case remains agnostic of the trigger — allowing for reuse across multiple delivery mechanisms.

4.2 Driven Adapters: Implementing Contracts

Driven adapters fulfill the contracts defined by ports in the core. These ports declare what the use case needs — but not how that need is satisfied.

Driven adapters may include:

- Database repositories

- Event publishers

- Email and notification services

- File uploaders

- Monitoring or tracing systems

Each adapter is tied to a specific tool or protocol, but the use case interacts with it only through its abstract port.

[{Example: MongoDB repository implementing a port interface for persistence}]

This decoupling allows for infrastructure changes without modifying the core logic.

4.3 Replaceability and Adapter Composition

The key strength of this architecture is that adapters are replaceable by design. The use case doesn’t depend on Flask, MongoDB, RabbitMQ, or any specific provider. It depends only on clearly defined ports.

| Change | Required Domain Changes |

|---|---|

| MongoDB → DynamoDB | None |

| Flask → FastAPI | None |

| REST → Event trigger | None |

| Python → Rust | Only reimplement use cases |

This structural decoupling enables teams to evolve, refactor, or replatform without fear of breaking core logic. It also allows for multiple implementations per port — useful in testing, A/B deployment, or migration strategies.

At runtime, the application composes the system by wiring ports to adapters and mapping entry points to use cases via configuration, dependency injection, or factories.

Figure 2. A Flask-driven adapter invokes a use case that interacts with multiple infrastructure adapters such as RabbitMQ, a third-party provider, and MongoDB.

4.4 Entry Points and Mapping Patterns

As shown in Figure 1 (Section 3), entry points serve as driving adapters. They:

- Receive and transform external input

- Invoke the appropriate use case

- Return or emit structured output

This mapping pattern supports:

- Multiple triggers for the same logic

- Replacing delivery frameworks without touching core logic

- Simplified onboarding and testing

Entry points remain thin, stateless, and easily replaceable — just like the adapters they depend on.

By separating business logic from integration details, adapters give us the ability to build systems that last — not just by surviving change, but by embracing it.

5. Metadata as Architectural Communication

In sustainable systems, architecture is not just code — it’s communication. The challenge is not only how to design clean boundaries, but also how to make those boundaries visible and actionable across a growing team.

This is where metadata plays a critical role.

5.1 Beyond Configuration: Metadata as Design Intent

Metadata is often associated with configuration — formats like YAML or JSON used for deployment or runtime behavior. But in this context, metadata is something more: a declarative expression of architectural decisions.

It can describe:

- Which use cases exist

- How they are triggered (e.g., HTTP, cron, events)

- What ports they depend on

- What behaviors are expected (e.g., retries, authentication, observability)

By externalizing this information, we make the system more inspectable, introspectable, and automatable — not only for machines, but for humans too.

5.2 Communicating Across Roles

Metadata becomes a shared artifact that connects different contributors around a common source of architectural truth:

- Architects use it to express constraints and intent

- Developers use it to scaffold and implement aligned components

- DevOps and SREs use it to provision triggers and observability pipelines

- QA teams use it to drive test scenarios from declared behaviors

Instead of tribal knowledge, the architecture becomes part of the source code, in a form that is versioned, validated, and diffed like any other asset.

This metadata acts as living documentation: it evolves alongside the system, reflects the current state of architectural decisions, and remains actionable by both humans and machines. It removes the gap between design and implementation — architecture is no longer hidden in slide decks, but encoded directly in the system itself.

5.3 Visual Models and Metadata Synchronization

Metadata can be both derived from and transformed into visual representations of the system architecture. This bidirectional flow creates opportunities for:

- Generating sequence diagrams or component maps from a YAML file

- Updating metadata based on edits in a visual tool

- Validating structural consistency between planned models and implemented use cases

This empowers architects to design in visual terms, while keeping implementation aligned through structured metadata.

5.4 AI-Augmented Architecture and Development

When metadata encodes system intent, AI tools can reason about the architecture. This unlocks use cases such as:

- Auto-generating boilerplate or adapter scaffolding from high-level descriptions

- Identifying inconsistencies or gaps in declared ports and implementations

- Proposing improvements to dependency structure or reuse opportunities

- Surfacing architectural drift as the system evolves

As teams scale and complexity grows, these kinds of intelligent assistants help reinforce discipline and provide real-time architectural feedback.

Metadata is not just a tool — it’s a medium for architectural thinking at scale. It turns the implicit into the explicit, enabling systems that are not only well-structured, but also well-understood and open to automation.

6. Call to Action: Embrace the Bisslog Mindset

If the principles outlined in this article resonate with you, and you’re seeking a practical way to implement them, consider exploring Bisslog — a lightweight, dependency-free library that embodies the Hexagonal Architecture (Ports and Adapters). Bisslog isn’t just a tool; it’s a mindset that promotes clean separation between domain logic, application, and infrastructure, allowing for flexibility and scalability in your microservices architecture.

🔗 Explore Bisslog Resources

Bisslog Core Library

A lightweight Python library implementing Hexagonal Architecture principles.

👉 GitHub RepositoryIntroducing Bisslog

An in-depth look at building sustainable microservices with Bisslog.

👉 Read the ArticleBisslog Mindset vs. Dependency

Understanding Bisslog as a mindset rather than just a dependency.

👉 Read the Article

By adopting Bisslog, you can build microservices that are not only robust and testable but also adaptable to change, ensuring long-term sustainability and maintainability of your software systems.

7. Common Pitfalls and Anti-Patterns

Even with a clear architectural vision, it’s easy to fall into traps that compromise sustainability. This section highlights frequent mistakes that undermine separation of concerns and weaken the architecture over time.

❌ Embedding Business Logic in Controllers

Problem: Placing logic directly in HTTP handlers or Lambda functions tightly couples business rules to delivery mechanisms.

Consequence:

- Difficult testing (requires full stack context)

- Fragile when changing frameworks

- No reuse across different triggers (e.g., REST vs. events)

Better: Delegate to a framework-agnostic use case and pass only validated input.

❌ Bypassing Ports for External Communication

Problem: Calling infrastructure tools (e.g., a database or queue) directly from use cases.

Consequence:

- Domain logic becomes dependent on third-party libraries

- Testing becomes harder

- Portability is lost

Better: Define an abstract port and implement it via a driven adapter.

❌ Treating Metadata as Just Configuration

Problem: Using metadata only to drive deployment or environment-specific settings.

Consequence:

- Missed opportunity to express architectural intent

- Teams may lose alignment on how features are structured

Better: Treat metadata as a living architectural contract — one that defines use cases, triggers, ports, and expected behavior.

❌ Allowing Frameworks to Leak into the Core

Problem: Use of request objects, HTTP response codes, or ORM models inside core logic.

Consequence:

- Tight coupling

- Inflexible to change

- Reduced reusability and testability

Better: Interact with frameworks only through adapters; keep core logic pure and decoupled.

Avoiding these anti-patterns reinforces the values of Clean and Hexagonal Architecture — keeping your system modular, testable, and adaptable.

❌ Moving Use Case Logic into Adapters

Problem: Performing parts of the business logic — such as validation, enrichment, or decision-making — inside adapters rather than the use case.

Consequence:

- Logic becomes fragmented across multiple adapters

- Risk of duplication (e.g., multiple adapters repeating the same validation)

- Harder to reason about or modify behavior centrally

Better: Keep all business rules — including validations and decisions — inside the use case. Adapters should be dumb translators, not decision-makers.

8. Conclusion: Designing for Longevity, Not Just Delivery

Sustainable microservice architecture is not defined by the tools we use, but by the discipline of separation we maintain.

By placing business logic at the center — decoupled from frameworks, infrastructure, and runtime triggers — we create systems that are easier to test, evolve, understand, and operate. Clean and Hexagonal Architectures provide complementary lenses for achieving this structure. Use cases act as orchestration units, ports define expectations, and adapters isolate technology-specific implementations.

But beyond code structure, this architecture impacts how teams work:

- Architects design with clarity, through ports and metadata.

- Developers build with focus, shielded from noisy infrastructure details.

- QA and Ops automate from shared contracts, not assumptions.

- The system becomes an artifact of collaboration, not just implementation.

Crucially, metadata acts as a living bridge — enabling both human understanding and machine automation. It makes architecture a first-class citizen of the development process, opening the door to tooling, validation, and intelligent augmentation.

This is not about dogma or purity — it’s about sustainability.

Systems that can adapt without being rewritten.

Teams that can grow without fragmenting.

And code that expresses intent, not just behavior.

By investing in separation, we invest in software that lasts.

If architecture is the art of decisions that resist time, then sustainable systems are those built to preserve intent — no matter what changes around them.

References

- Martin, R. C. (2012). Clean Architecture: A Craftsman’s Guide to Software Structure and Design. Prentice Hall.

- Cockburn, A. (2005). Hexagonal Architecture. Retrieved from https://alistair.cockburn.us/hexagonal-architecture/

- Evans, E. (2004). Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software. Addison-Wesley.

- Fowler, M. (2004). Inversion of Control Containers and the Dependency Injection pattern. Retrieved from https://martinfowler.com/articles/injection.html

- Newman, S. (2015). Building Microservices: Designing Fine-Grained Systems. O’Reilly Media.

- Hohpe, G., & Woolf, B. (2003). Enterprise Integration Patterns: Designing, Building, and Deploying Messaging Solutions. Addison-Wesley.

- Feathers, M. (2004). Working Effectively with Legacy Code. Prentice Hall.

- Richardson, C. (2018). Microservices Patterns: With examples in Java. Manning Publications.

- OpenTelemetry. https://opentelemetry.io

- AWS Lambda Documentation. https://docs.aws.amazon.com/lambda/latest/dg/welcome.html

- YAML Ain’t Markup Language (YAML™). https://yaml.org

Note: This list includes both foundational works and practical references that informed the architectural patterns described in this article.